Introduction

As UVM testbenches evolve from simple setups to complex, multi-layered environments, configuration management becomes one of the most critical and confusing aspects of maintaining control and flexibility.

Every testbench you build, regardless of its scale, has configurations in it, deciding which agents are active, what address range the DUT uses, what random constraints to apply, which sequences to run, and much more.

In early stages, these configurations may seem straightforward. It always starts with just a few knobs here and there. But as the verification environment matures, these knobs multiply across components, sequences, and even DUT-level parameters. Managing them cleanly and systematically is key to scalable and debuggable testbenches.

This article provides a structured view of configurations in UVM — how to classify them, the different methods to apply them, and how to avoid common pitfalls. We start by asking two questions.

What are we configuring?

How are we configuring?

What are we configuring?

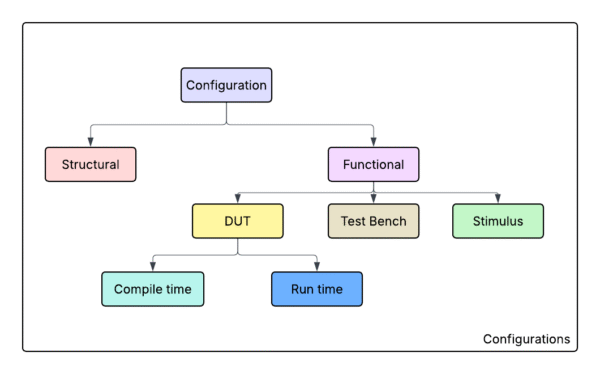

Based on what we are configuring, configurations can be classified into two main categories:

Structural Configuration: Deals with the testbench's setup and build. It defines the "what" and "where" of your testbench components.

Functional Configuration: Deals with the testbench's behavior and functionality. It defines "how" your components and stimulus should operate. We can further classify the functional configuration in to following picture.

Structural configuration

It deals with the testbench setup and build architecture. This is about which components are instantiated and how they are interconnected in different configurations of your environment. In other words, structural config controls the “shape” or topology of the verification environment. Examples include: enabling or disabling entire agents, adding or removing scoreboards or monitors, using a different environment topology for different tests, or instantiating multiple copies of a sub-environment based on configuration. As the testbench evolves to handle multiple modes or protocols, structural configuration techniques help avoid duplicating code by programmatically building the desired structure.

Take a look at the above picture. We have 3 modes of operation and in each mode we want a different environment with different hierarchy of components in it. In old verilog days, we have to make a separate module for each mode and instantiate it. We can swap these modules with conditional compilation macros. This approach requires you to re-compile everytime you want to change the mode of operation.

With introduction of Object oriented programming in SystemVerilog, we can now change the mode of operation without re-compiling the code again. We can change the structure programmatically. In modern test benches, there are often several env’s, and within each env, there are multiple hierarchical components that needs to be structurally put together based on the configuration.

So structural configuration is first target in configuration. We will discuss different approaches for configuration in later part of the article (How are we configuring). For now, let’s move on to second target of configuration: Functional configuration.

Functional Configuration

While structural configuration was about the “physical” composition of the testbench, the functional configuration deals with how the testbench and DUT operate, things like modes of operation, protocol settings, sequence behaviors, etc. Functional configurations can be subdivide into three areas:

Testbench-Specific Configuration: Settings that affect the testbench components’ functionality but do not directly configure the DUT. Examples: agent modes (active vs passive), enabling coverage or scoreboarding, timeouts, check enabling, etc. These configurations adjust how verification components behave.

DUT Configuration: Settings that configure the design under test itself. This could include DUT parameters (compile-time or run-time), default register values, protocol modes, or anything that the DUT hardware sees as a configuration. For example, a DUT might have a register to set its operating mode, or the test might need to run with different DUT parameterizations (like different data widths).

Stimulus Configuration: Settings controlling the stimulus generation – which sequences to run, how random or directed the stimulus is, sequence item parameters, number of transactions, etc. This category ensures the inputs to the DUT can be altered per test scenario without modifying sequence code.

All these configurations are “functional” because they affect the behavior of the simulation (what stimulus is driven, what the DUT does, what checkers do) rather than the presence/absence of components. Let’s look at each sub-category in detail.

Testbench-Specific Configuration

This configuration tailors the verification components themselves. For example, you might want to run one test with an agent in passive mode (monitor only, no driver) and another in active mode; or turn off functional coverage in certain runs to save time; or adjust a monitor’s sampling rate. None of these change the DUT – they only affect the testbench operation. UVM encourages making such aspects configurable so the same testbench can cover many scenarios.

DUT Configuration

DUT (Design Under Test) configuration refers to controlling the DUT’s operating parameters or initial settings via the testbench. This can range from compile-time parameters (like a bus width or FIFO depth) to runtime settings like register values, mode selects, or memory contents that the DUT relies on. Essentially, anything that the DUT considers a configuration input falls here. Let us breifly touch over the compile time and run time DUT configurations.

Compile-Time Parameters: If your DUT has compile-time parameters (for example, parameter ADDR_WIDTH = 32; in the RTL), you generally handle different values by recompiling or using a simulation +define that sets the parameter before simulation starts. UVM itself doesn’t override elaboration parameters. Once the design is elaborated, the parameters are all fixed and cannot be changed. Remember, when you need to change the parameters, you need to recompile the design again.

DUT Register and Mode Configuration (Runtime): Many DUTs have control registers or modes that need to be initialized or varied per test. UVM provides the Register Layer for a systematic way to handle registers, but even without it, you can simply use sequences to program the DUT. For example, if the DUT has a register MODE that must be 3 for a certain scenario, you can write a small sequence at the start of the test to set that value (via the bus interface or backdoor).

The question is how to integrate this into the configuration mechanism. One way is to treat these desired register settings as part of a DUT config object. You could define a dut_config class with fields like default_mode, enable_featureX, etc., fill it in the test, and then have an initialization sequence that reads dut_config and applies the settings to the DUT (by writing registers or driving DUT inputs).

This sequence could be launched automatically in the test or by the env. Alternatively, if using UVM register model, you might load the desired mirror values and call a write().

Stimulus Configuration

Stimulus configuration covers how we control the generation of stimulus sequences and data in the testbench. This includes which sequences run, in what order, with what settings, and how the sequence items are constrained or directed. The goal is to allow various tests to produce different stimulus scenarios without hard-coding those inside the sequences themselves. UVM’s philosophy is that sequences are like “recipes” for stimulus, and tests can choose which recipe to use or tweak certain ingredients.

Key aspects of Stimulus Config:

Selecting which sequence to execute for a given test.

Parameterizing sequences (e.g., number of transactions to generate, specific distributions of fields, enabling or disabling certain sub-sequences).

Controlling sequence items’ attributes at runtime (for instance, in a random traffic sequence, maybe one test wants mostly reads, another mostly writes – this could be a knob).

Possibly switching sequences on the fly or having reactive sequences that adjust based on config.

These are some broad areas that we typically configure in UVM test bench. So far we only discussed what exactly we are configuring and their classification, now let’s focus on How are we configuring or the approaches to configuration in UVM test benches.

How are we configuring?

Let’s begin by enumerating different options available for controlling testbenches. This is not an exhaustive list but I believe these methods are definitely most commonly used.

Command line defines

Command line plusargs

Factory overrides

Configuring with UVM config DB

Configuring with config objects with UVM config DB

Configuring with config objects without UVM config DB

Command line defines

Command line defines are preprocessor macros that are passed to the SystemVerilog compiler. These defines are processed during the compilation phase, before the code is actually compiled.

They provide a mechanism for conditional compilation, allowing different code paths to be included or excluded based on the presence of these defines or substitute values in the source code. The defines are global in scope,. This is particularly useful for enabling debug features but I prefer not to use defines for testbench configuration other than specific debug related cases. Read more about macros here.

Below code snippet serves as an example of configuration using defines. Remember, you need to recompile the code for the defines to take effect.

// Compile with: +define+DEBUG_MODE +define+MAX_TRANSACTIONS=1000

module my_module;

// Check if DEBUG_MODE is defined

`ifdef DEBUG_MODE

// This code is only compiled if DEBUG_MODE is defined

initial begin

$display("Debug mode is enabled");

end

`endif

// Check if MAX_TRANSACTIONS is defined and use its value

`ifdef MAX_TRANSACTIONS

parameter int MAX_TX = `MAX_TRANSACTIONS;

`else

parameter int MAX_TX = 100; // Default value

`endif

endmodule : my_moduleCommand line plusargs

Command line plusargs are runtime arguments that are passed to the simulation using a `+` prefix in the command line. Unlike compile-time defines, plusargs are evaluated during simulation runtime, allowing for dynamic configuration without recompiling the code.

They are accessed using SystemVerilog’s built-in functions $value$plusargs() for retrieving values or $test$plusargs() for checking their presence. Plusargs are commonly used in UVM testbenches for selecting tests, enabling features, or passing configuration values that need to be determined at simulation start time.

// Run with: +test_name=my_test +enable_coverage=1 +num_iterations=50

module testbench;

string test_name;

int num_iterations;

bit enable_coverage;

initial begin

// Check if plusarg exists (returns 1 if found, 0 if not)

if ($test$plusargs("enable_coverage")) begin

enable_coverage = 1;

$display("Coverage collection enabled");

end else begin

enable_coverage = 0;

end

// Retrieve string value from plusarg

if ($value$plusargs("test_name=%s", test_name)) begin

$display("Test name: %s", test_name);

end else begin

test_name = "default_test";

end

// Retrieve integer value from plusarg

if ($value$plusargs("num_iterations=%d", num_iterations)) begin

$display("Number of iterations: %0d", num_iterations);

end else begin

num_iterations = 10; // Default value

end

// Use the retrieved values

if (enable_coverage) begin

// Enable coverage collection

end

end

endmoduleFactory Overrides

// Base component class

class base_driver extends uvm_driver#(my_transaction);

`uvm_component_utils(base_driver)

function new(string name = "base_driver", uvm_component parent = null);

super.new(name, parent);

endfunction

task run_phase(uvm_phase phase);

`uvm_info("DRIVER", "Base driver running", UVM_MEDIUM)

endtask

endclass

// derived class for protocol-specific driver

class protocol_driver extends base_driver;

`uvm_component_utils(protocol_driver)

function new(string name = "protocol_driver", uvm_component parent = null);

super.new(name, parent);

endfunction

task run_phase(uvm_phase phase);

`uvm_info("DRIVER", "Protocol driver running", UVM_MEDIUM)

endtask

endclass

// Agent that creates driver using factory

class my_agent extends uvm_agent;

base_driver driver;

function void build_phase(uvm_phase phase);

super.build_phase(phase);

// Factory will use override if set, otherwise creates base_driver

driver = base_driver::type_id::create("driver", this);

endfunction

endclass

// Test with type override - applies to ALL instances of base_driver

class test_with_type_override extends uvm_test;

my_env env;

function void build_phase(uvm_phase phase);

super.build_phase(phase);

// Set type override: all base_driver instances become coverage_driver

base_driver::type_id::set_type_override(protocol_driver::get_type());

env = my_env::type_id::create("env", this);

endfunction

endclass

// Test with instance override - applies to specific instance only

class test_with_inst_override extends uvm_test;

my_env env;

function void build_phase(uvm_phase phase);

super.build_phase(phase);

// Set instance override: only env1.agent.driver uses protocol_driver

base_driver::type_id::set_inst_override(

protocol_driver::get_type(), "env1.agent.driver");

env = my_env::type_id::create("env", this);

// Instance override takes precedence over type override

endfunction

endclassConfiguration with UVM config DB

// Setting configuration values in config DB

class my_test extends uvm_test;

my_env env;

virtual interface my_interface vif;

int num_transactions = 100;

function void build_phase(uvm_phase phase);

super.build_phase(phase);

env = my_env::type_id::create("env", this);

// Set virtual interface for all agents in all environments

// Wildcard "*" matches any component name at that level

uvm_config_db#(virtual interface my_interface)::set(

this, "*.env.agent", "vif", vif);

// Set a configuration value for a specific component path

uvm_config_db#(int)::set(

this, "env.agent.driver", "num_tx", num_transactions);

// Set a configuration object

my_config cfg = my_config::type_id::create("cfg");

cfg.enable_coverage = 1;

uvm_config_db#(my_config)::set(

this, "*.env.agent", "cfg", cfg);

endfunction

endclass

// Getting configuration values from config DB

class my_agent extends uvm_agent;

virtual interface my_interface vif;

my_config cfg;

int num_tx;

function void build_phase(uvm_phase phase);

super.build_phase(phase);

// Get virtual interface - empty string "" means current component path

// The config DB searches up the hierarchy to find matching config

if (!uvm_config_db#(virtual interface my_interface)::get(

this, "", "vif", vif)) begin

`uvm_error("AGENT", "Virtual interface not found in config DB")

end

// Get configuration object

if (!uvm_config_db#(my_config)::get(this, "", "cfg", cfg)) begin

`uvm_error("AGENT", "Config object not found")

end

// Get integer value (with default if not found)

if (!uvm_config_db#(int)::get(this, "", "num_tx", num_tx)) begin

num_tx = 10; // Default value

end

endfunction

endclass

Configuration with config object using UVM Config DB

While uvm_config_db variables work well for simple types, configuration objects provide a more structured and maintainable approach for complex configurations. A configuration object is a class that contains all the configuration parameters for a component, making it easier to manage and pass around related configuration data. Look at the example below.

// Environment configuration containing agent configurations

class env_config extends uvm_object;

`uvm_object_utils(env_config)

agent_config master_agent_cfg;

agent_config slave_agent_cfg;

bit enable_scoreboard = 1;

bit enable_coverage = 1;

function new(string name = "env_config");

super.new(name);

master_agent_cfg = agent_config::type_id::create("master_agent_cfg");

slave_agent_cfg = agent_config::type_id::create("slave_agent_cfg");

endfunction

function void configure();

// Configure master agent

master_agent_cfg.agent_name = "master";

master_agent_cfg.is_active = 1;

master_agent_cfg.num_packets = 10000;

// Configure slave agent

slave_agent_cfg.agent_name = "slave";

slave_agent_cfg.is_active = 0; // Passive agent

slave_agent_cfg.num_packets = 0;

endfunction

endclassConfiguration objects (passing handles without config db) and other ad-hoc methods

// Configuration object class

class my_config extends uvm_object;

bit enable_coverage;

int num_transactions;

string test_mode;

`uvm_object_utils(my_config)

function new(string name = "my_config");

super.new(name);

endfunction

endclass

// Test that uses direct handle passing

class my_test extends uvm_test;

my_env env;

my_config test_cfg;

function void build_phase(uvm_phase phase);

super.build_phase(phase);

// Create configuration object

test_cfg = my_config::type_id::create("test_cfg");

test_cfg.enable_coverage = 1;

test_cfg.num_transactions = 100;

test_cfg.test_mode = "direct";

// Create environment and pass config directly

env = my_env::type_id::create("env", this);

// Method 1: Use public method

env.set_config(test_cfg);

// Method 2: Direct assignment

env.cfg = test_cfg;

endfunction

endclass

// Environment that receives and forwards config

class my_env extends uvm_env;

my_config cfg;

my_agent agent;

`uvm_component_utils(my_env)

function new(string name = "my_env", uvm_component parent = null);

super.new(name, parent);

endfunction

function void set_config(my_config env_cfg);

this.cfg = env_cfg;

endfunction

function void build_phase(uvm_phase phase);

super.build_phase(phase);

// Create agent and pass config directly

agent = my_agent::type_id::create("agent", this);

agent.cfg = cfg; // Direct assignment

endfunction

endclassNow that we have seen different methods of configurations. Let us understand which fits for specific type of configuration target. Broadly, all the compile time configuration targets are done with defines. All runtime configurations are done with UVM config DB either with individual configuration values or via configuration objects. The configurations that need to change more frequently can be passed on using plusargs. These plusargs are captured and then configured using UVM config DB. If the changes are as big as swapping a component or data item then Factory would be right method. See the map below for how different methods go well with different configurations.

Conclusion