What You Actually Use Every Day

If you read most explanations of the UVM factory, they begin with APIs. They explain set_type_override_by_type(), show a minimal example, and stop there. What’s missing is the architectural context: Why experienced verification engineers depend on the factory in real projects.

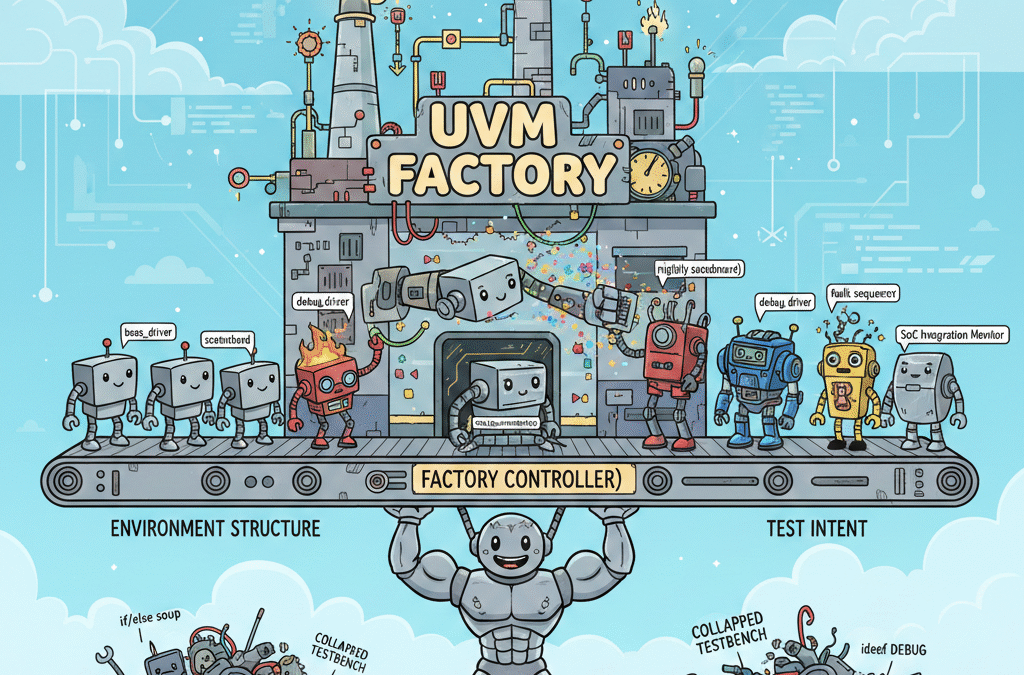

The reason is simple: verification environments evolve faster than RTL. Debug builds behave differently from regression builds. Stress testing behaves differently from clean protocol runs. Block-level verification behaves differently from SoC integration. If every behavioral variation required editing the environment, your testbench would collapse under its own weight within a year.

The factory exists to prevent that collapse.

At its core, the UVM factory is controlled late binding. When you write:

driver_h = base_driver::type_id::create("driver_h", this);You are not directly constructing base_driver. You are delegating the decision to the factory. The environment asks for a base type. The factory decides what concrete implementation to return. That indirection is deliberate as it separates environment structure from test intent.

The environment defines hierarchy and connectivity. The test defines behavioral variation. The factory is the boundary between those two worlds. Once you see it this way, the factory stops being an advanced feature and starts being a practical architectural tool.

Where the Factory Shows Up in Everyday Work

The most useful aspects of the factory are not exotic. They appear in routine project work, often without engineers explicitly calling them “design patterns.”

Debug Variants Without Polluting Stable Code

Consider a driver that is stable and validated. One day, a corner-case failure appears. You need additional logging, deeper protocol checks, or state tracing. The temptation is to insert debug flags, add conditional branches, or sprinkle ifdef DEBUG across the class.

That decision seems harmless in the moment, but it permanently pollutes your production component. The disciplined alternative is behavioral substitution. Create a debug-specific extension:

class debug_driver extends base_driver;

// extra checks and logs

endclassThen override it at the test level:

set_type_override_by_type(base_driver::get_type(), debug_driver::get_type());The base driver remains clean. The debug logic is isolated. The test controls behavior. Nothing structural changes. No environment edits are required. The architecture stays intact. This is factory usage at its most practical.

Regression Modes and Swappable Scoreboards

Real regressions rarely operate in a single mode. Smoke tests (or sanity or environment tests) prioritize speed. Nightly regressions prioritize thoroughness. Performance runs minimize overhead. Attempting to embed all those modes into a single scoreboard class inevitably leads to conditional complexity.

Instead, define behavioral variants: a lightweight checker for speed and a full reference model scoreboard for depth. The environment requests a base scoreboard type. The test decides which implementation to activate.

This approach removes mode flags from infrastructure. Checking depth becomes part of test intent rather than embedded environment logic. Over time, this separation dramatically improves maintainability.

Fault Injection Without Rewriting the Agent

Constrained-random verification eventually requires aggression: illegal transactions, protocol violations, timing stress, malformed traffic. None of these belong in the production driver or agent.

Rather than mutating stable components, create specialized extensions for stress testing and override them only in the relevant tests.

The production environment remains stable. Stress logic remains isolated. Behavioral variation is controlled entirely at the test layer. This isolation is what allows large environments to evolve safely across multiple projects.

Per-Instance Behavioral Control in Multi-Agent Systems

In multi-channel DUTs, not all interfaces behave identically. One channel may require latency injection. Another may require protocol perturbation. A global type override is too blunt for this situation.

In this case, Instance overrides provide surgical precision:

set_inst_override_by_type( "env.agent[2].driver", base_driver::get_type(), slow_driver::get_type());Only one hierarchical path changes behavior. The rest of the system remains untouched.

Without instance overrides, engineers often introduce conditional logic based on instance IDs inside drivers. That approach gradually erodes architectural clarity. Instance-level factory control prevents that decay.

Block-Level to SoC Reuse

The most underestimated practical benefit of the factory appears during vertical reuse. At block level, agents are active and scoreboards are comprehensive. At SoC level, agents may become passive and checking may shift toward integration monitors.

If components are constructed directly, reuse demands environment edits. If type_id::create() is consistently used, SoC tests can substitute implementations without touching infrastructure. The hierarchy remains stable. Only behavior adapts to the situations. This is the difference between a project-specific testbench and a reusable verification platform.

The Boundary That Makes Everything Work

Across all these examples, one pattern remains consistent: structure does not change. Ports do not change. Connectivity does not change. Only behavior changes.

The factory is a behavioral substitution mechanism. It is not a structural mutation engine. Respecting that boundary is what keeps UVM environments scalable. When the factory is used to change architecture rather than behavior, complexity grows exponentially. When it is used strictly for behavioral variation, architecture remains stable while tests evolve.

Override Discipline, Resolution Order, and Architectural Control

Now we come to second part of the article. If Part 1 explained when to use the factory, Part 2 explains how to use it without damaging your architecture. The factory itself is deterministic. Problems arise from undisciplined overrides.

Understanding Resolution Order

The factory supports two primary override mechanisms: type overrides and instance overrides. Resolution follows a strict hierarchy. Instance overrides take precedence over type overrides. If neither applies, the originally requested type is constructed.

A type override replaces all future creations of a given base type and an instance override affects only a specific hierarchical path:

// type override

set_type_override_by_type(base_driver::get_type(), debug_driver::get_type());

// instance override

set_inst_override_by_type("env.agent[2].driver",

base_driver::get_type(),

slow_driver::get_type());Understanding this resolution order eliminates much of the mystery surrounding “unexpected” behavior. The factory does exactly what it is instructed to do.

Architectural Rules That Prevent Chaos

The factory becomes dangerous only when overrides are scattered and implicit.

First, overrides belong in tests. Components define infrastructure. Tests define variation. When components internally perform overrides, predictability is lost.

Second, prefer instance overrides when possible. Global type overrides should be intentional and rare. Instance overrides provide precision and reduce unintended side effects.

Third, never use the factory to introduce structural variation. If two components require different topology or hierarchy, that is a configuration or parameterization problem. The factory should not compensate for architectural instability.

Fourth, inspect the factory state during debug. A simple factory.print() reveals active overrides. Many debugging sessions waste hours because engineers assume behavior rather than verifying override resolution.

Finally, avoid layered overrides across inheritance hierarchies of tests. When base tests override one implementation and derived tests override again, clarity disappears. Override logic should remain centralized and explicit.

Common Failure Modes in Real Projects

Several recurring issues surface across teams.

The first is missing registration. Without proper uvm_component_utils registration, overrides silently fail.

The second is late overrides. Overrides must be applied before component construction, typically in the test’s build phase. Applying them after build has no effect.

The third is using the factory for configuration knobs. Minor variations such as timeout values, feature flags, or coverage enablement belong in configuration databases or parameters. The factory replaces implementations. It does not toggle settings.

The Mindset Shift That Matters

The most practical aspect of the UVM factory is not the API. It is the architectural mindset it enforces. A scalable verification environment has stable structure and replaceable behavior. Tests control variation. Infrastructure remains clean. Overrides are deliberate and visible.

Without the factory, environments become one-off project code. With disciplined factory usage, they evolve into reusable verification platforms capable of surviving multiple product cycles.

The factory is not a trick. It is a control mechanism for architectural evolution.

Used casually, it creates hidden coupling. Used with discipline, it becomes one of the most practical tools a DV engineer uses every day. And in large projects, that distinction determines whether your testbench scales or collapses.